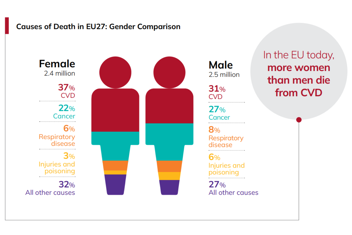

When it comes to the heart, biology is only part of the story, and gender may tell the rest. Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the leading cause of death for women in Europe, with 37% (2.4 million) of deaths in women attributable to CVD compared to 31% in men, according to recent data from the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). This underscores a grim reality: more women than men die from CVD in the EU today.

Despite this, women have been under-recognised, underdiagnosed, and underserved in cardiac care for decades. So, are women with CVD simply different? Or are they also unequal or, worse, discriminated against?

This was the eye-opening question explored in a recent JACARDI Masterclass led by Dr. Héctor Bueno, co-leader of Work Package 7 "Data availability, quality, accessibility and sharing" of JACARDI. His talk poses a challenge to reconsider what is truly known about women and heart disease.

Same heart, different story

Women are not just biologically different from men; they also face worse outcomes in cardiovascular disease. They’re more likely to die from a heart attack and often experience longer delays in receiving treatment. Yet, they remain underrepresented in clinical trials, leaving critical knowledge gaps and contributing to unequal care.

Several biological differences help explain these disparities. Women tend to have lower body weight and height, which influences how drugs are metabolized through liver and kidney function. Oestrogens affect immune and vascular responses, and anatomically, women have smaller hearts and narrower coronary arteries, factors that can complicate diagnosis and intervention, especially in conditions like coronary artery disease, where diagnostic tools and treatment protocols are largely based on male physiology.

Symptoms of heart disease also differ. Instead of the typical chest pain seen in men, women often report fatigue, nausea, or shortness of breath, signs that can be overlooked or misinterpreted. Additional risks come from pregnancy-related conditions, menopause, and hormonal disorders like polycystic ovarian syndrome and premature ovarian insufficiency, all of which elevate long-term cardiovascular risk.

The systemic nature of these disparities cannot be ignored, advised Dr Bueno. Women consistently receive less evidence-based care, are taken less seriously in emergency settings and are treated later. The structural bias within healthcare systems, built largely around male models of care, results in worse outcomes for women.

EU 27 Cardiovascular Realities 2025 (European Society of Cardiology)

A new prescription: inclusion

According to Dr Bueno, the path forward must address these inequities head-on through a multifaceted approach. First, improving data collection is essential, with a focus on conducting inclusive research that captures gender-specific differences in CVD.

Additionally, clinical guidelines must be adapted to reflect the unique needs of women; for instance, those who have experienced pregnancy-related disorders should receive regular cardiovascular risk assessments and appropriate follow-up care. Finally, education plays a crucial role: both healthcare providers and the public need to be made aware of the gender disparities in CVD to foster a more equitable approach to prevention, diagnosis, and treatment.

Recognising gender differences in CVD is about enhancing care to address the unique needs of everyone. At JACARDI, as well as our partners at JA PreventNCD, we are deeply committed to ensuring that prevention strategies are both equitable and inclusive, paving the way for better outcomes for all.

Author: Cristina Cebrián Méndez, CNIC, Spain - member of the JACARDI communication and dissemination team.